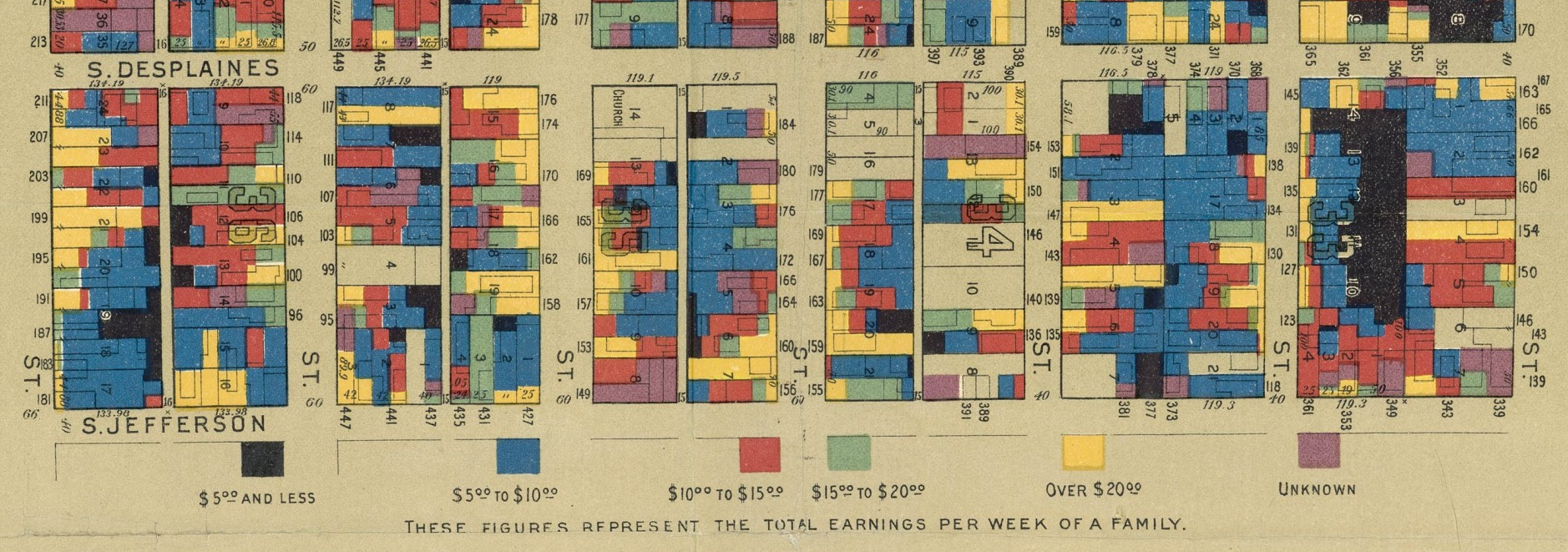

Community organizing is typically taught in human service programs, especially in social work courses. Social work in the US is rooted in the work of Jane Addams who, in the late 1800s, organized and served a neighborhood community in Chicago. Google “Jane Adams Hull House Chicago maps” to see some of the geographic maps of the neighborhoods she served. Today, with information technology’s embrace of social media, human service professionals can take advantage of new community building tools.

One recent tool, Nextdoor, is a private social networking tool that currently links 96,000 geographic communities in the US. Nextdoor’s mission is “to use the power of technology to build stronger and safer neighborhoods.” Only verified members of a geographic community, who use their real names, can participate. Privacy is a big concern: whilst government agencies like the police can post informational messages on topics such as burglaries, they cannot see or join the neighborhood conversations. While my city departments post announcements, I have not seen any from a social service agency: for example, stating what services they can provide to a neighborhood.

As you would expect, common topics range from lost dogs and cats, locating a trusted plumber, soliciting a good home for a no longer needed bicycle, finding a home for animals of a resident who must move into a nursing facility and so on. Nextdoor messages can be delivered via a daily digest, email, or by logging in. It also supports private email between residents. One recent example of the power of Nextdoor to connect neighbors was when I received a Nextdoor email from someone who had taken in a wandering dog and needed to find the owner. When I was outside a little later, I heard someone driving slowly down the street calling a pet’s name from her car window. Both I and my neighbor stopped her and told her about the Nextdoor post. My neighborhood pulled out her smartphone and showed her the post, saw that the Nextdoor description matched her dog, replied to the post saying she had found the owner and needed an address. A happy reunion occurred and the lady with the lost dog joined Nextdoor.

We need research on how community building tools like Nextdoor can be used by human service professionals. For example, using Nextdoor data to develop a pattern of how people are using Nextdoor to build their neighborhoods. Many research questions come to mind. Do certain online strategies work better than others in building neighborhoods? Is there a typical progression of neighborhood building over time? Do online neighborhood communities spawn face-to-face communities, or vice versa. Does knowing about neighborhood crime make one feel more or less safe? Are their easy ways to prevent overly aggressive postings, flaming, name calling, and other problems associated with text postings that can easily be misinterpreted? An offensive posting in our neighborhood was quickly removed a few days ago by someone given that authority by Nextdoor. Do tools like Nextdoor work best when neighbors have desktop PCs, or are smartphones the communication device of choice to build neighborhoods? Are there indicators of successful online neighborhood building? Tools like Nextdoor have a wealth of data that human service professionals with big data skills can mine to discover important knowledge about online and face-to-face community building. I’m sure the Journal of Technology in Human Services would welcome research that incorporates use of these new online neighborhood building tools into our knowledge base.

Dick Schoech

Professor & Editor Emeritus, Journal of Technology in Human Services